Who I am and why you should listen to me

The story of how I went from programming Snake on a Commodore 16 to leading award-winning mobile titles, and why I believe Focus and Positioning are the most underrated skills in game development.

The moment that shaped my entire life

I was six years old the first time I saw a video game. I was with my family at a seaside bar in Italy (my home country), where we had stopped for a quick break on a spring weekend in 1984.

In a corner, there was a big black box that was blinking with coloured lights. I didn’t know what it was, but it pulled me in like gravity.

I was too short to see over the arcade cabinet, so my mother lifted me up. On the screen, an angel shot beams of light at alien monsters. I had never seen anything like it. The experience was immersive, and I stared at the screen for a few minutes. When my uncle offered me a coin to play, I felt like I was being handed a ticket to another dimension.

That moment would define the rest of my life. Not just because it sparked a love for video games, but because it showed me the power of interactive experiences: how technology can create entire worlds that make us feel, think, and dream.

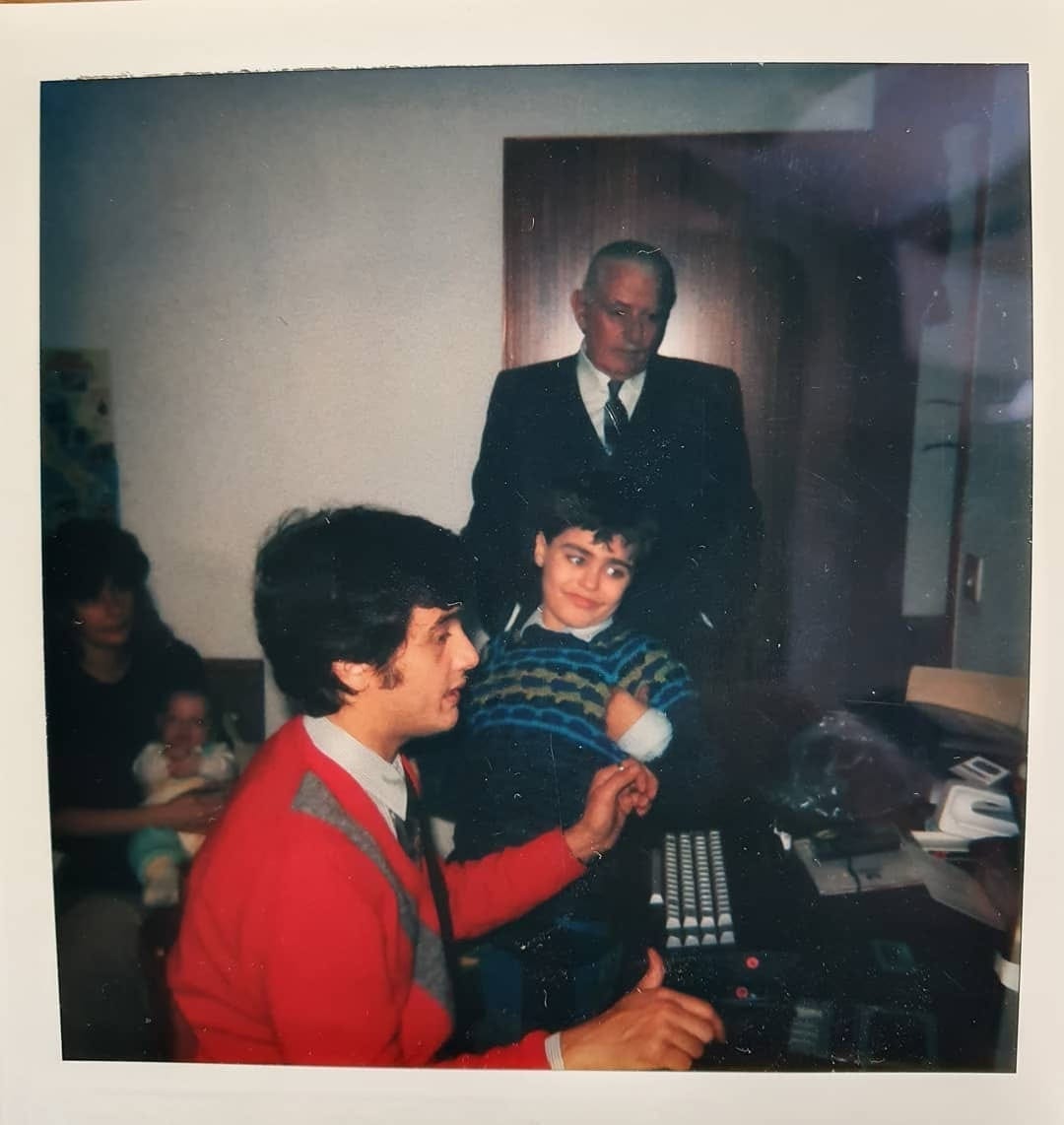

That Christmas, my father bought me a Commodore 16. It came with a cassette reader and a thick, mysterious manual titled “Commodore 16 for You – BASIC 3.5”. While other kids were learning to ride bikes or play soccer, I was deciphering computer code.

Soon, my curiosity evolved into action. Gaming magazines in the 1980s often published full source code listings for simple games. One Saturday morning, my father brought home an issue that featured the classic Snake game. We spent the day painstakingly copying lines of code into the Commodore’s rudimentary text editor. It was tedious, meticulous work, but it felt like magic.

It took me and my dad a whole weekend. At that time, there weren’t any save options, so I left the computer turned on the all night. I still remember the neon-blue glow of the monitor in the middle of the dark room.

When we finished typing the code, I ran the game before saving it to the tape cassette (no hard drives!). The intro scene popped up, and I started playing. After a few seconds, the screen went black and I soon realised I had lost everything.

I’m still not sure what happened, but I believe we made some mistakes copying the code and introduced a bug somewhere that crashed the game.

But in that heartbreak was a lesson: always save your work. I still do it every five minutes.

From there, my journey into programming and problem-solving accelerated. I began writing small games, tweaking borrowed code, and imagining entire stories I wanted to turn into experiences.

At school, I was the odd one out. When we were asked to write a book review, I submitted a review of the BASIC programming manual. My teacher looked at me as if I were from another planet. But that was fine because I was building a language of my own.

Martial arts, mental clarity, and my first job

Parallel to my interest in tech, I developed a lifelong passion for martial arts. I began training at an early age, drawn to its discipline of both mind and body. Martial arts taught me focus, perseverance, humility, and self-control. Those lessons would become invaluable, especially in moments of burnout and crisis later in my life. And Focus became the guiding thread running through my journey, the discipline to ignore distractions and commit fully to one path.

As I moved into my teenage years and early adulthood, I balanced school, martial arts, and my obsession with technology. I began working as a bartender in my parents’ restaurant during university, where I was studying Computer Science.

First, my dad placed me at the till, where I greeted customers and collected bills. Then he gave me some marketing work that I initially found annoying. At first, it was small tasks, like designing and printing promotional flyers. Soon, I moved on to managing events and taking on bigger responsibilities. The restaurant grew rapidly, and after a couple of years, we opened a second one. It was hard to work and study at the same time, but I loved what I did.

Without realising it, I was learning about business, team management, customer service, and brand storytelling. Skills that would later become central to my identity as a founder, strategist, and product leader.

Ubisoft years: the dream realised

By the late 2000s, I had one clear goal: work at a major game studio and learn everything I could about the development pipeline, from design and prototyping to marketing and distribution.

One of my mates at university told me that Milestone, a racing game company in Milan, was looking for a junior software engineer. The problem was, I didn’t like big cities…too much chaos.

I was puzzled.

Then I discovered that Ubisoft had a studio there and was hiring as well. So I thought: if I had to live in a city I didn’t like, I might as well be there for the best.

So I applied to both Milestone and Ubisoft.

Milestone rejected me. Ubisoft didn’t.

I was over the moon.

On May 21, 2007, I packed my car and drove to Milan. I remember the day vividly. It felt like stepping into a new world.

At Ubisoft, I was surrounded by raw talent and relentless ambition. My first project was My Secret Diary for the Nintendo DS. It was a game designed for teenage girls. Not exactly the dream project, but it gave me an incredible opportunity to work on voice chat, one of the game’s most technically challenging features.

That’s also when I learned the true meaning of crunch time: long nights, missed weekends, constant stress.

But I pushed through and earned my place on the team.

After shipping the game, I was exhausted. I needed a break, and, on top of that, the salary wasn’t great. I asked for a raise, but they pushed back. So I quit and decided to walk the St. James route to find some clarity in my life.

I must have been very good at what I was doing, because the company called back, asking if I was interested in going to Casablanca to lead the sequel of the game (or maybe they simply couldn’t find anyone else crazy enough to move to Morocco for a year).

Either way, I felt ready for something new and accepted the offer (with a big salary increase). It would be my first experience abroad and my first leadership role.

Unfortunately, due to the 2008 financial crisis, the project was canceled after a few months. I was called back to Milan, where I joined a new project: We Dare for the Nintendo Wii.

The game made headlines, not for its gameplay but for its controversial marketing campaign. It was ultimately banned in the UK, a lesson in how public perception can override product intent. It was one of my first reminders that how you position something publicly can define its fate just as much as the product itself.

Then came Kinect.

Microsoft was preparing to revolutionise gaming with motion-sensing technology, and our Milan studio was selected to create one of only six launch titles. It was a big opportunity, but it came with an intense deadline: six months.

What followed was the most intense crunch of my life, including sixteen straight days in the office, from 9 a.m. until late at night.

But we did it.

MotionSports shipped on time. The game launched with Kinect and achieved solid commercial success.

Still, I was burned out, physically and emotionally. I needed space, and this time it meant more than just one month walking in Spain. I had always wanted to see the different nuances and cultures of the world before globalisation erased them. As time went on, cities and cultures seemed to blur together, losing their uniqueness.

Ted Simon is a famous writer who traveled twice around the world on a motorbike: when he was 42 and then when he was 70. Comparing the world of today with the world of thirty years earlier, he describes his disappointment in this way:

I think my disappointment arises out of a genuine sense of loss. Obviously I can't regret the passing of South American dictators, or the end of apartheid, or the unseating of Haile Selassie, or even the independence of Zimbabwe. But I do regret that my son will never be able to dance with the Turkana as I once did, that China has lost its mystery, that it is possible to travel from one end of Africa to the other without seeing a wild animal that isn't protected, and that all the empty beaches I once loved are full.

In my small way, I felt the same sense of loss and I believed this was the right moment to act.

So I resigned (yes, again).

South America, Fallout Shelter, and an unexpected revelation

That month spent in Spain walking the St. James route taught me that the best way to travel is to do it slowly. So I decided to travel without taking any flights. I booked a passage on a cargo ship from Barcelona to São Paulo, sold everything I had (including my car), and planned a 50cc motorcycle trip through South America.

For six months, I travelled through Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Bolivia, and Peru, reconnecting with the world and with myself.

After six months of traveling on my motorbike, my bank account was depleted, so I decided to stop and settle in Santiago, Chile, and look for a job. I thought it would take ages, considering I was in a foreign country, without a work visa, and without speaking the language fluently (Spanish). I started doing small jobs: working as a waiter at private parties for Santiago’s wealthy families, guiding wine tours in English, and so on. Finally, after just one month, I found a full-time job at Behaviour Interactive’s South American office as a game engine programmer.

It was a lot of fun.

Then Unity came out, and within months the in-house engine team was dismantled and reassigned to other projects.

My leadership skills stood out, and after leading a few minor projects, I soon found myself heading the development team for the mobile game Fallout Shelter.

We didn’t know it then, but Fallout Shelter would become an award-winning mobile game, generating daily revenues of over $2 million and surpassing industry giants like Candy Crush in the U.S. and U.K. Apple Stores. It won awards, and introduced a new generation to the Fallout universe.

It was a phenomenon but, more importantly, it was a turning point for me.

Fallout Shelter taught me that even a great game needs more than just mechanics. It needs branding, timing, distribution, and deep customer insight. Understanding your audience is not a bonus, it’s the foundation. This was my epiphany: mechanics don’t make a game successful, positioning does. Once I saw it, I couldn’t unseen it, and I knew I’d never build or join a project without applying it again.

This insight hit me like a lightning bolt. I had to understand marketing, not just casually, but at the deepest level possible.

Becoming a student again: Marketing and the psychology of success

It was 2014, and I decided that if I wanted to continuously improve myself, I had to live in one of the three countries where video games were most developed. At the time, those countries were the United States, Japan, and England. I also wanted to reconnect with friends and family, so I chose England.

This time, I didn’t want to work for a big company. I already had a clear idea of the entire video game production process, and now I wanted to understand how to create and grow a company. But most importantly, I wanted to learn marketing, the one skill that I realised would make the difference between having a successful game or not.

I started devouring books, attending conferences, and I enrolled in training programs.

I studied with Frank Merenda, the Europe’s foremost direct marketing expert. Through him, I learned the principles of brand positioning from Al Ries, and I immersed myself in direct response marketing with Dan Kennedy. And I had the chance to study with, and meet, the genius Jay Abraham, whose strategic insights have generated over $9 billion for his clients.

Marketing became more than a skill. It became a lens through which I saw everything: product, user experience, pricing, retention, and virality.

The lesson was clear: a game doesn’t sell just because it’s fun. It sells because people understand why it matters: to them, in their context, for their goals.

But more than anything, I fell in love with the concept of positioning, as defined by Al Ries and Jack Trout. I carried their books everywhere, on crowded trains during my commute, in the quiet of late evenings, reading them again and again until the ideas sank in. The two books, Focus and Positioning, became my compass, not just for marketing but for life itself.

And when I attended an on-line course with Al Ries, the master himself, it cemented my conviction. From that moment on, positioning wasn’t just a concept I admired, it was the principle I chose to build everything upon.

Armed with this new perspective, I joined Supersolid, a small mobile gaming startup in London. We were ten people in one room. Four years later, we were fifty people with our own floor.

We launched multiple games that achieved millions of downloads, all without a publisher. We controlled our own destiny because we understood product–market fit, and player psychology. We became known as the mobile gaming company that made restaurant and food games.

Supersolid confirmed my belief: indie developers don’t need a publisher. They need clarity. They need a system. And they need to treat marketing as seriously as game design.

Most developers focus on creativity and only scramble for help once the game is done. But by then, it’s often too late. The issue is that the video game industry is no longer like it was in the ’80s, when there were only a few games. Today, it’s a mature industry, and competition is fierce.

I was seeing a lot of video game companies struggling, including a rise in layoffs. Using positioning, I started to analyse successes and failures, even at big companies, and I identified a common pattern. The heart of that little boy inside me, who was mesmerised in front of that old arcade cabinet in 1984, was broken.

So I took a big leap of faith, and in autumn 2019 I started a video game consulting company focused on positioning.

S**t happens!

I was over the moon. I loved what I was doing, and I had the freedom to work anywhere and at any time I wanted.

Things were going well too. My articles were gaining traction, indie developers were contacting me for help, and I started receiving invitations to speak at video game conferences all around Europe. In January 2020, I set up my office at the Tentacle Zone in London, a small co-working space owned by the video game company Payload Studios.

Then Covid hit.

I still remember it as if it were yesterday. It was February, and I was travelling to Rimini, Italy, to attend a three-day marketing event with Frank Merenda and Jay Abraham. I landed in Bologna, and at the gate a few people wearing clinical suits were taking our temperature.

I was puzzled.

Later, I discovered that we were very close to the red zone created by the Italian government to quarantine the Covid outbreak.

The last day of the marketing event was cancelled by the Italian government. All public events were now banned.

I was lucky enough to get a return flight to London, and after a few weeks Covid hit the UK…and the whole world. All the conferences I had been invited to were now canceled, and my clients disappeared. After just two months, I canceled my contract with the Tentacle Zone and locked myself down in my apartment.

At the same time, I was struggling with my health. The rainy weather in London aggravated my sinusitis, and everything felt like it was collapsing.

Beyond games: A new life

Frustrated by the gaming industry’s monetisation trends and burnout culture, and with my savings almost depleted, I decided to take my skills elsewhere.

I joined a startup that was making the first augmented reality headset for the construction industry. It wasn’t by chance, and I picked this company for only one reason: positioning. They were the first company to build an AR headset designed to disrupt construction processes and workflows. My expertise in interaction design and real-time rendering translated perfectly.

I spent almost four years climbing the ladder, from software engineer to vice president.

Amid all this, life continued. I found love, and I became a father for the first time.

And fatherhood gave me a new reason to fight for what I love. I wanted to create a future where my son wouldn’t have to choose between passion and security, where he could pursue his dreams without fear.

My creativity and passion led me to Luminari Roli, where I worked on revolutionary music technology, blending expressive hardware with immersive software. Once again, positioning played a key role: Roli was the first company to create a light-up keyboard and companion app to teach piano. By this point, I had a rule: if a company didn’t have a clear, differentiated position in its market, I wouldn’t join or work with them.

In the meanwhile, my passion for video games continued to whisper in my ear (as Stephen King says), and I spent the little free time I had learning about what was happening in the gaming industry. The constant layoffs were still making me upset. It hurt to see developers pouring their time into games that would never see the light of day.

Here I am again

Games are not just entertainment. They are how we imagine. How we connect. How we build meaning in a chaotic world.

But even the best games fail when creators don’t know how to communicate their vision.

So I decided to revive my video game positioning idea and launch this newsletter.

I want to bring my 20 years of experience in video games and my knowledge of positioning to help developers not just build better games, but build games that succeed.

For two decades, focus kept me moving forward, and positioning gave me the clarity to choose the right battles. Every success I’ve had comes from applying those two principles relentlessly.

Because every great idea deserves to find its audience. Every creator deserves a shot at impact.

And every player deserves to discover a game that changes their world. It happened to that six-year-old kid in 1984 in Italy: a moment of magic that shaped a lifetime.

And it will happen again.

So let’s do it. Together.